Ban on export of non-basmati rice by India: Policy options to transform rice-based agri-food systems

- Aug 18, 2023

- 6 min read

Updated: Aug 21, 2023

Aminou Arouna, Gaudiose Mujawamariya, Abdulai Jalloh and Baboucarr Manneh

Africa Rice Center (AfricaRice)

On July 21st, India, one of the major rice exporters in the world announced the ban on export of non-basmati rice. Annually, India exports between 30 and 40% of the rice in the world and the majority of importing countries are in Africa. The decision of ban on non-basmati rice exports will lead to increase of rice price and food and nutrition insecurity in many countries in Africa. The situation is alarming as these countries are already facing inflation following input price hikes since 2020 due to both effects of COVID-19 pandemic and the conflict between Russia and Ukraine. This communique calls for an urgent action from African countries to avoid further deterioration of food insecurity and achieve rice-self-sufficiency.

Overview

Since 2020, the world has been facing two major crises: the most serious public health crises in the century, caused by the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic and the war between Russia and Ukraine and. The direct consequence of these crises has been the increase of the prices of fertilizer and staple foods such as wheat and rice. Even though the number of food insecure people in the world has been decreasing until 2014 and then remained stable between 2014 and 2019, food insecurity has drastically increased since 2020 due mainly to these two crises. It is estimated that about 735 million people in the world faced hunger in 2022 representing 122 million more food insecure people compared to 2019, before the global pandemic. Unfortunately, the announcement of India on July 21st, 2023, one of the major rice exporters in the world, to ban export of non-basmati rice with immediate effect has increased the uncertainty on food and nutrition security especially in developing countries since it is putting new pressure on the price of major staple foods such as rice. India accounts for 30-40% of world rice exports over last three years (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Proportion (in percentage) of rice exports from India and the rest of the world.

Source: APEDA Agri-Exchange Mundi, 2022

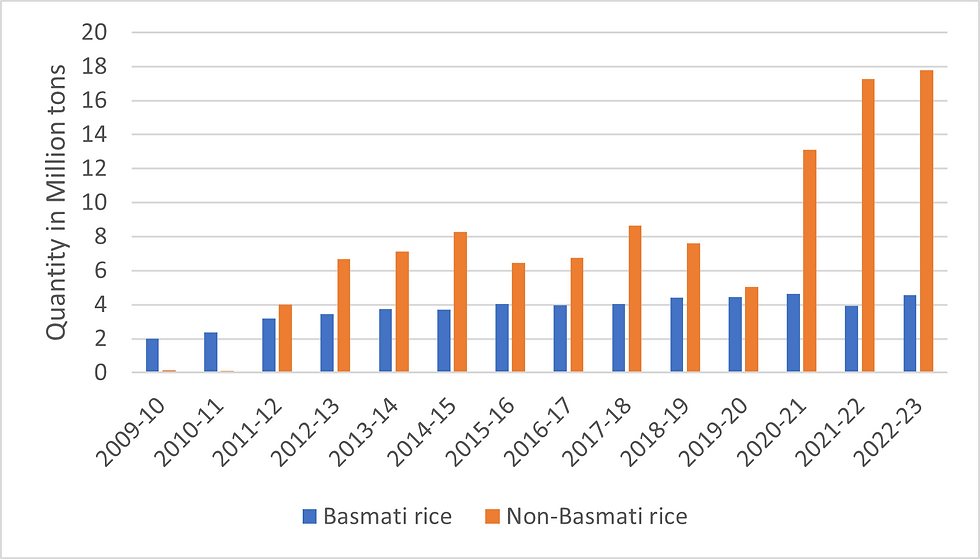

India’s rice shipments reached a record 22.2 million tons in 2022 including 17 million tons of non-basmati rice (Fig. 2), more than the combined shipments of the world’s next four biggest exporters of the grain (Thailand, Vietnam, Pakistan and the United States). India emerged as the world’s largest rice exporter in 2011-12, displacing Thailand from its leadership position following the lift of a four-year ban on exports of non-basmati rice in 2011. As opposed to exports of around 100,000 tons of those varieties in 2010-2011, exports soared to 4 million tons in 2011-2012. Exports of basmati rice in those two years stood at 2.3 and 3.2 million tons, respectively. Since then, India has risen to dominance in global rice markets. The continuous increase in exports of non-basmati varieties reached 8.2 million tons in 2014-15, and after a fall to 6.4 million tons in the subsequent year, it rose again to 8.6 million tons in 2017-18. The increase has continued in the export of non-basmati rice by India to reach 17.8 million tons in 2022 (about 30% of rice world export). This largely due to the fact that over a relatively long period domestic demand for rice has remained below domestic supply. However, due to severe drought in the 2022-2023 season in India, the government of India, as in 2011, took the decision to ban the export of non-basmati rice effective July 21st, 2023. This decision will induce a shortage of rice in the world market and will contribute to actual inflation in many countries especially in Africa where more than 40% of rice consumption is imported. India is exporting non-basmati rice varieties to several countries including Benin, Cote d’Ivoire, Senegal, Togo, Guinea, Madagascar, Cameroon, Djibouti, Somalia, Liberia, Angola, Mozambique and South Africa. These countries are amongst the 20 top importers of non-basmati rice from India. In 2022, African countries imported 11.3 million tons of non-basmati from India representing 64% of India’s total export (Fig 3).

Figure 2. Quantity of basmati and non-basmati rice exported by India (in million tons)

Source: APEDA Agri-Exchange Mundi, 2022

Figure 3. Percentage of non-basmati rice exported by India to Africa (in million tons)

Source: APEDA Agri-Exchange Mundi, 2022

The ban on export of non-basmati rice varieties threatens a food and nutrition security in many countries and especially the poorest ones. In Africa, rice represents the basic food for more than 750 million people. In addition, consumers are already facing the negative effects of high international food prices. The potential shortage in the supply of major food items such as rice, combined with rising consumer prices, will likely push back millions of people, especially in Africa, into deep food insecurity and poverty. To avoid a repeat of the 2007-2008 food crisis and that of the past two years, urgent policy measures are required to transform rice-based food systems.

The risks faced by the rice food market in Africa

Rice is the fastest growing staple food in Africa, especially for West Africa, where it is the main source of calories compared to other cereals. The ban on export of non-basmati rice varieties by India, in combination with the on-going crisis between Russia and Ukraine in which Russia has withdrawn from the agreement on cereal exports from Ukraine, is expected to lead to considerable decrease in availability of rice and other cereals on global markets leading to increase in consumer prices. This will likely result to food and nutrition insecurity.

Decrease in rice supply in global market

The ban on export of non-basmati rice varieties by India will certainly lead to shortage of rice supply in the world market. In the context of low reserves of rice in the world, the implication of the ban is that at least one third of rice exports will be missing in the world market. This will affect the supply in the importing countries which are mainly in Africa. In 2022, 13 countries in Africa (Benin, Cote d’Ivoire, Senegal, Togo, Guinea, Madagascar, Cameroon, Djibouti, Somalia, Liberia, Angola, Mozambique and South Africa) are among the first 20 non-basmati rice importers from India.

Risk of food and nutrition security

The decrease in rice supply is likely to lead to an increase in consumer prices and evidence shows that the consumption of rice is likely not to decrease due to price increase. With rice scarcity and high consumer prices, the share of food expenditure will increase in the household budget. As consumers in many countries are already facing high inflation since early 2022 because of both COVID-19 pandemic and the crisis between Russia and Ukraine, it is likely that higher rice prices will lead to increase in food and nutrition insecurity. It is imperative, therefore, to take emergency measures to increase local production to offset the expected dramatic reduction from rice exporting countries.

Preventing food and nutrition insecurity through emergency interventions to transform the rice agri-food systems in the time of uncertainty

Increasing local supply and transforming rice agri-food systems to compensate for the uncertainty of the world markets due to the ban of non-basmati rice export by India and the on-going crisis between Russia and Ukraine is the only way to avoid food insecurity and use this opportunity to achieve the rice self-sufficiency policy pursed by many countries in Africa. In addition to on-going efforts in the different countries, these interlinked objectives can be achieved if the following additional measures are undertaken:

Short term measures

Purchase of quality seed of climate resilient and consumer-preferred rice varieties by governments and distribution to rice farmers. The required quantity will depend on potential rice area in each country.

Subsidize and monitor the price of appropriate fertilizers for rice production.

Provide rice production and processing loans at lower rates to farmers and processors.

Promote good agricultural practices through massive training of rice farmers for improving productivity.

Scale the efficient use of fertilizers through site- and personalized recommendations using digital tools such RiceAdvice.

Medium- and long-terms measures

Increase investment in irrigated rice production in different countries.

Encourage the development of regional fertilizer manufacturing plants to reduce dependency on imports.

Increase access of rice smallholder farmer to credit for production and processing.

Increase mechanization of production, harvest and post-harvest activities.

Reduce postharvest losses of staple food crops.

Develop sustainable food security policies and investment plans.

Increase investment in research for development.

Conclusion

Against the background of Russia’s withdrawal from the cereal exportation agreement with Ukraine, the ban on exports of non-basmati by India is likely to cause consumer price hikes especially in the import-dependent countries which are mainly in Africa. This will likely lead to food and nutrition security. As in previous times of uncertainty, AfricaRice is calling on policy makers and development partners to redouble their efforts to increase the resilience and productivity of rice-based agri-food systems for food and nutrition security in Africa.

Download the PDF English version here

Download the PDF French version here

Comments